CRISPR is a powerful gene editing tool, but how do consumers view this technology if it were to deliver cranberry products with less added sugar and improved flavor? Would they “buy into” CRISPR cranberries?

These are just some of the questions that Dr. Karina Gallardo, Co-PD and Professor in the School of Economic Sciences at Washington State University, and her team are trying to answer in their latest survey looking at consumers’ willingness to pay for certain traits in cranberry products.

In their upcoming paper, “Would Consumers Accept CRISPR Fruit Crops if the Benefit has Health Implications? An Application to Cranberry Products”, the team outlines that, despite cranberry products being viewed as healthy, added sugar to cranberry products can deter consumers. Gene editing tools such as the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) offer a way to breed cranberries with lower acidity or increased sweetness from natural sugars, cutting down the need for added sugars, but would consumers be open to buying products resulting from the use of this technology?

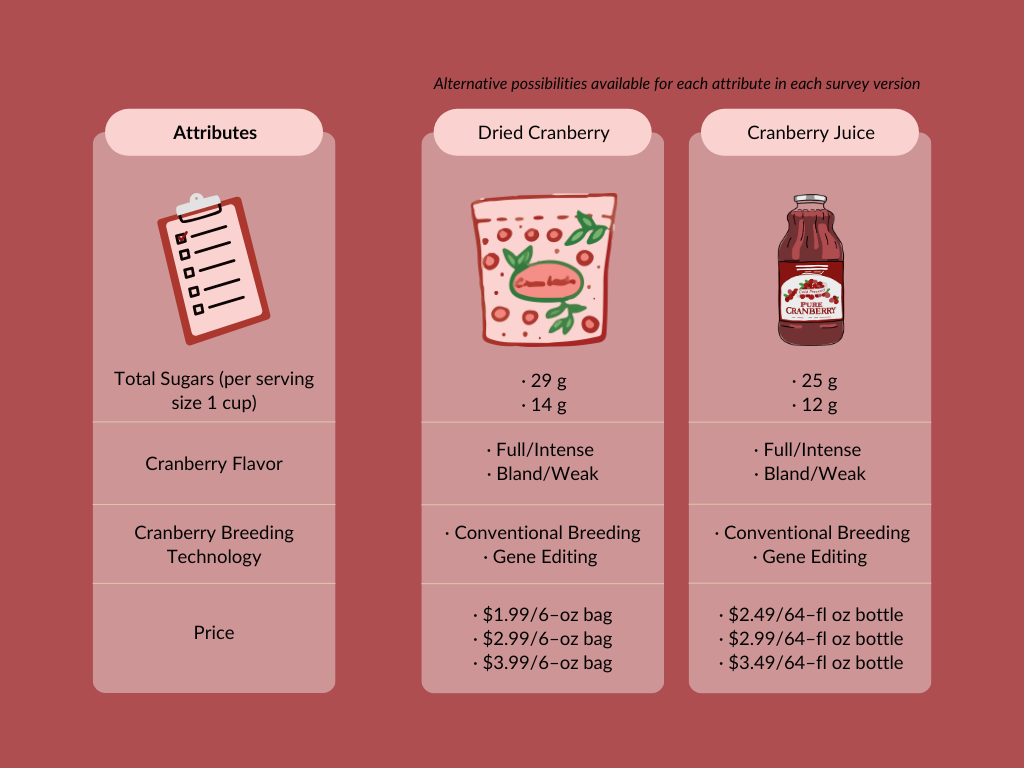

For their survey, Gallardo and her team questioned consumers on their willingness to pay for sugar content, CRISPR, and cranberry flavor intensity for two cranberry products under different health-related information treatments.

Respondents were divided into groups with different treatments, or information presented to them before answering the questions. Treatment 1 was the control group with no additional information presented to the respondents. Treatment 2 briefly described the health benefits of cranberries (positive). Treatment 3 focused on the benefit of limiting sugar consumption, specifically noting “added sugars” (negative). Treatment 4 showed respondents the scripts from both 2 and 3, with the team expecting the health benefit information will offset the negative “added sugars” information.

“We also explained what total sugar content is. We explained cranberry flavor intensity is the combination of sensations influenced by taste, aroma, look, and texture. Then we explained what conventional breeding and CRISPR is,” Gallardo said.

This was a choice experiment, where respondents were asked to imagined themselves presented with two cranberry product options in a grocery store setting. Gallardo gave the example:

Option A is a bag of sweetened and dried cranberries with intense cranberry flavor, 14 grams of sugar, and genetically edited, selling at a price of $3.99. Option B is a bag of sweetened and dried cranberries with weak cranberry flavor, 20 grams of sugar, and bred through conventional methods at a price of $2.99. Which of these two would you choose?

“We repeat this and we present a random combination of these attribute levels. For example, question one can have [the above example] combination but question two can have 14 grams of sugar with a bland/weak flavor, conventional breeding, and a cost of $2.99. Or the 29 grams of sugar, with a full/intense flavor, gene editing and a $3.99 price,” Gallardo said. “We randomly combined these four levels of attributes. That allows us to estimate the value that people have for each of these attributes.”

According to responses, the team noticed people are willing to pay less if sugar content information is presented on the product label, if CRISPR has been used, and if cranberry flavor is weak. However, compensated valuation analysis of products with different attribute levels indicated that consumers were willing to pay a premium for cranberry products with reduced added sugar content through CRISPR breeding and full/intense cranberry flavor relative to products with added sugar content, conventionally bred, and weak/bland flavor. Respondents that received information treatments highlighting cranberries’ health benefits and recommendations to limit sugar intake were willing to pay less for regular sugar content cranberries even when compared to CRISPR-bred cranberries

Gallardo has a couple possible explanations for this in terms of regular versus reduced sugar content. Some of this might have to do with consumer perception of a healthy products and what they should offer.

“We have other studies that show people are more demanding with products that have a ‘halo effect’ [of health], like if I expect this product is going to be healthy, why the heck does it have more sugar than I should have? They are stricter with that,” Gallardo said. “But if this was ice cream, for example, they wouldn’t care that it has regular sugars, because it’s an indulgence. With a ‘halo effect’ it is like a regiment or lifestyle.”

The other explanation is the impact of the negative and positive treatments. Gallardo says the team initially anticipated that when presenting both, the positive treatment would offset the negative, resulting in a smaller discount. But that wasn’t the case.

“In any of the cases when you present both sets of information, the discount is larger. This is telling us that the positive information about the health benefits of the product is not offsetting the negative information of the added sugar,” Gallardo said. “The FDA said if you put on the front of the label the health claims of cranberries, it is going to offset the negative influence of the added sugar additional line in the nutrition facts panel. These [responses show] it doesn’t offset. People are willing to discount more, even though they know cranberries have a [health benefit]. But knowing that there is added sugars, people don’t care, they’re willing to discount more than just cutting out the sugars alone.”

When comparing CRISPR to conventional breeding, Gallardo notes that consumers view this gene-editing tool more favorably if it is able to reduce added sugars and enhance flavor. The team calculated the value of a cranberry product made with conventional breeding, that has added sugar content and weak/bland flavor compared to a product that is CRISPR-bred, with reduced added sugar and full/intense flavor.

“By kind of combining all the goods for CRISPR-bred and all the bads with conventional, people actually are willing to pay more for CRISPR,” Gallardo said. “Our results showed people are willing to pay more for CRISPR cranberries with reduced added sugar because the reduction of added sugar is viewed positively. This benefit [of reduced added sugar] offsets any suspicion or negativity they have with CRISPR because the aversion to added sugar is larger than for CRISPR.”

The team decided to delve further into the responses, with latent class analyses to identify variations in the acceptance/rejection of the different attributes of sweetened and dried cranberries and cranberry juice. They split the control group into three different classes: strong CRISPR rejection (class 1), mild CRISPR rejection (class 2), and the indifferent to CRISPR group (class 3). They looked at which groups were more willing to discount certain traits more than the others. The team wanted to identify what type of consumers were in these classes and how demographics like income or gender might vary among responses.

Respondents were recruited through Qualtrics’ consumer research panels. Gallardo’s team was given three demographics to control, including age, geographical representation, and income—which they wanted a close as possible to the United States breakdown of income. They also screen for shoppers who make the grocery purchasing decisions for their household.

“[The respondent] needs to make the decisions, even if they don’t consume themselves and are buying for somebody else in the house. For example, I want to hear from the mother that buys cranberry juice for her kids but doesn’t drink it herself.” Gallardo said.

The team also screened for how frequently people consumed cranberries and their knowledge of cranberry products. For the sweetened and dried cranberry questions, respondents needed to have consumed them in the past year. Cranberry juice questions required people to know the difference between cranberry cocktail juice blends and 100% juice.

For the sweetened and dried cranberries, they wanted to hear from a mix of shoppers who eat cranberries occasionally and those who are loyal consumers of sweetened and dried cranberries that consume them frequently.

“[Respondents that consumed cranberry juice] were more connoisseurs than those that consumed sweetened and dried cranberries, because we were asking specific questions about the difference between 100% juice and cocktail, and not everybody knows that.” Gallardo said. “Maybe that’s why [we observed] the differences in our results, right? [Consumers that drink] juice are more like the loyal consumers because they needed to know about these differences. Whereas [those that consumed] the sweetened and dried cranberries were the occasional consumers. That is a caveat in our study, we cannot compare side by side between juice and dry cranberries because our consumers are different, with juice drinkers more knowledgeable about the cranberry product than consumers of sweetened and dried cranberries.”

Gallardo says surveys like this show consumers are receptive of CRISPR methodologies if they are informed of the direct benefit to them and identify the main reason why they consume a product. This is good news for scientists working with CRISPR tools to expedite the creation of cultivars with enhanced characteristics such as improved flavor.

“For cranberries it is the health aspect. If you tell them, ‘Look, your cranberries are going to have less added sugars, if we bred them using CRISPR,’ I think they will be more acceptive to CRISP than if they didn’t know this information.” Gallardo said. “In the future, if you’re going to have a label or a law that dictates that you need to label CRISPR like genetically modified organisms (GMO), you need to put next to it ‘to allow the reduction of sugars’ or something like that.”