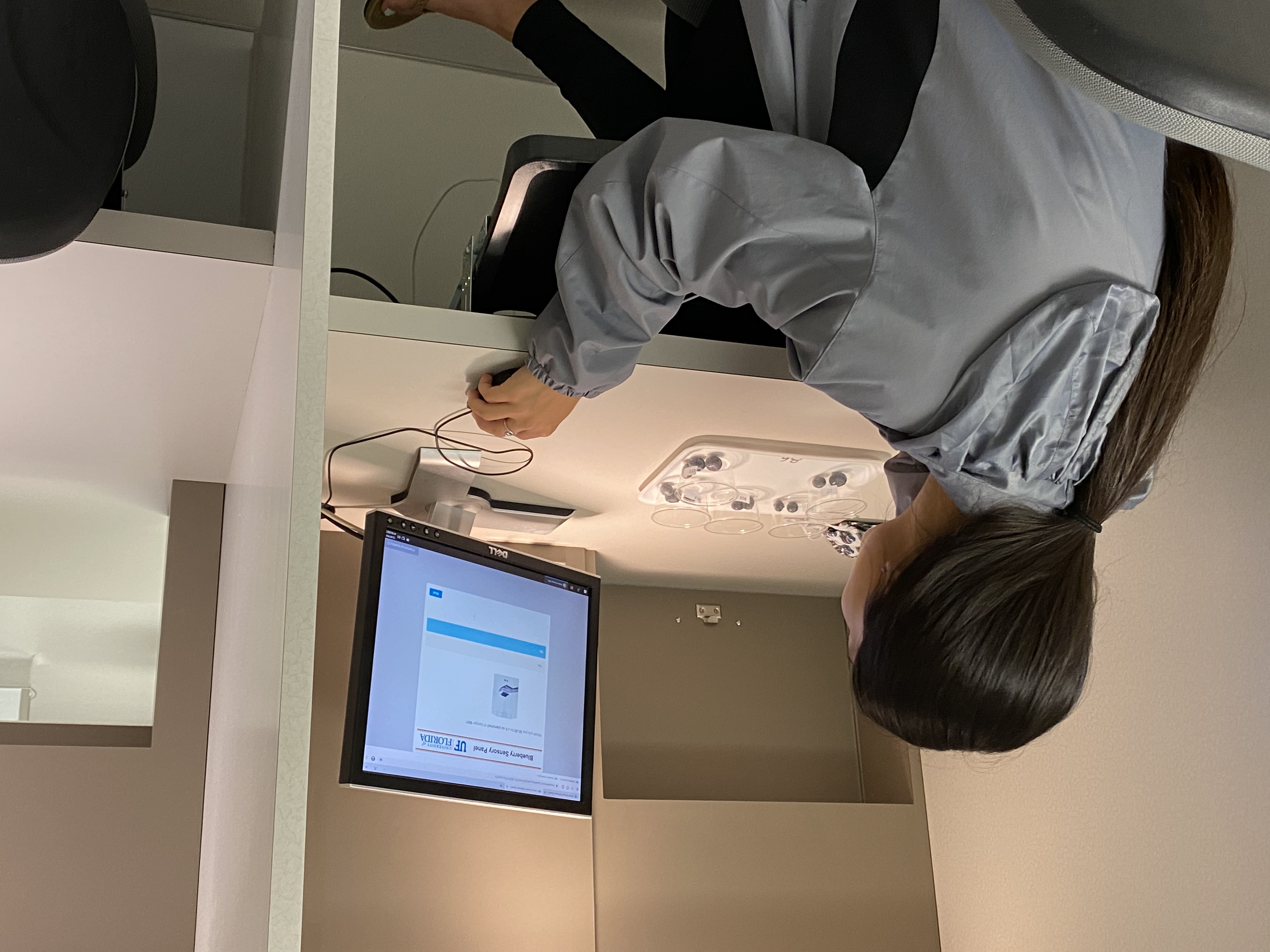

Sensory testing surveys offer important consumer feedback and useful insights to researchers. Dr. Charles Sims, Co-PI and Professor at the University of Florida (UF), recently concluded a blueberry sensory study to get a better understanding of consumers’ preferences when it comes to buying fresh blueberries.

Dr. Patricio Muñoz, Co-PD and blueberry breeder at UF, selected 20 blueberry cultivars from Florida that represented a wide variation in fruit quality. Sims then selected 90 participants to taste five of these cultivars at a time over four controlled tasting sessions.

“We do a lot of sensory testing with fresh fruits and vegetables, and I’ve worked with a lot of plant breeders in different crops,” Sims said. “What we really want to know in this project is how much did the participants, who define themselves as blueberry consumers, like the different blueberry cultivars."

Questions in the survey focused on how much panelists liked various characteristics of the samples they tried, such as texture, flavor, and how sweet or sour the berries are.

“We were asking specific sensory questions. And the bottom line is, how much do you like it overall? And is that driven mainly by appearance or texture or some flavor characteristic?” Sims said.

Dr. Karina Gallardo, Co-PD and Professor at Washington State University, and Dr. Elizabeth Canales, Co-PI and Assistant Professor at Mississippi State University, also contributed some questions about consumption and preferences in connection with consumer willingness to pay for blueberries with superior fruit quality.

“[Gallardo and Canales] measure willingness to pay—an important criteria to determine how much people really liked a blueberry,” Sims said. “It’s just a different way to ask people the same question, in my opinion, how much do you like it overall? And then how much are you willing to pay for it? That’s a little different approach to getting at the same thing, and they should correlate.”

Canales and Gallardo are attempting to connect panelists’ willingness to pay to their ratings of each sample in terms of taste, texture, and just general perceptions of fresh blueberry fruit quality.

“Hopefully, we’ll also be able to relate the willingness to pay to the actual physical measures of sweetness and acidity and texture” Canales said.

The team made sure to select a diverse group of participants in the survey, ranging from people that consume blueberries twice a year to some that consume blueberries more than once a month.

“We tried to select participants that would be considered an average shopper of blueberries—not an expert blueberry tester by any means,” Sims said. “And these people have not been trained in any way on what to look for in blueberries. Some people really value the appearance, some value the texture, and some people really want the good flavor, the sweetness, so each consumer may be looking for a different thing. But that’s all part of the big picture.”

They believe the testing showcased a good separation of results. Sims said that when Muñoz reviewed the results, the cultivars that scored highest were the ones that he would expect, while the ones scored the lowest were also predictably the poorest.

Sims also noted that when breeders select what they think are the best blueberries, it’s usually correct, but that it is good to have that substantiated by larger number of panelists who are average consumers.

“And so that’s where we come in. Instead of just depending on the breeder—who is normally right—we want to ask a broader pool of people,” Sims said. “This work really helped validate what the breeder has thought about all these years. I think for the stakeholders, this really provides a vote of confidence that the cultivars being selected are actually the ones that people really like.”

The next step is to replicate the survey with 20 cultivars from Oregon. The team notes allowing participants to taste the berries and then respond to questions can give more realistic and reliable answers since they’re using experience to inform their preferences.

But there are obstacles to tasting surveys. This survey will have a smaller sample size with testing locations only in Florida and Oregon. There are other factors that could weigh on a tasting survey, like participant fatigue, limited product, and where the product is coming from.

“The caveat of this study is that it is not generalizable, because of the logistics it’s impossible to have a participant pool of more than 100 or 200,” Gallardo said. “Because we want the blueberries to come as fresh as possible, since they don’t have much time off shelf life.”

Once all the surveying is complete, the team will compile the information to see what qualities consumers preferred in their blueberries and what correlates best with characteristics such as volatiles, sugars, and texture.

These results will help inform other initiatives within VacCAP as they work to better understand what makes a better berry both genetically and for consumers.

“The only reason to grow blueberries is to sell them to consumers. And the bottom line is if a consumer doesn’t like it, no matter what breeders do, nobody’s going to buy the blueberry,” Sims said.

Sims describes his team’s initiative as where “the agriculture meets the consumer” as they learn what consumers want out of their berries.

“If we know what the consumer likes, and we can start backing that up to the plant breeders, then they can use their genetic tools to really improve the cultivars more than just doing it haphazardly,” Sims said. “We feel like this is a more strategic approach. You know, if they have the best information—like these are the volatiles that they really need to be concerned about, this is the range of sugar levels they need to have, this is the range of texture—it just helps the breeders develop better blueberry cultivars.”