We often talk about how fruit quality is key when developing better blueberries. But what does fruit quality actually mean, and how is the Vaccinium Agricultural Coordinated Project (VacCAP) team working to improve those characteristics?

“We know that fruit quality is a complex and often elusive concept—which includes characteristics that are not only sensory related—in which the consumer is satisfied with the product they will eat.” Dr. Lara Giongo, Co-PI and head of the Berries Genetics and Breeding Unit at Fondazione Edmund Mach (Italy), said.

When discussing fruit quality in blueberry, that mostly refers to texture and flavor. These are the two main traits that Giongo’s team is developing methodologies to evaluate, but they are also looking at variability of the gene pool that they have available.

“Texture and flavor are connected,” Giongo said. “In blueberries, these two parameters are responsible for fruit quality, but they are quite difficult to assess objectively. We have to view sensory analysis from the perspective of understanding the consumers’ expectations of the food.”

However, objective assessment and standardizing methods of evaluating components like texture can enable downstream advances in breeding.

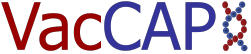

Giongo and her team have started to exchange their knowledge in this area—with a focus on blueberry firmness—with Dr. Penelope Perkins-Veazie, Co-PD, professor at North Carolina State University, and team members from the USDA. The methodology they have published on how to analyze texture in blueberry, as well as standardization methods that were tailored for blueberry, are at the heart of this exchange.

While recognizing the subjective nature of the term fruit quality, Giongo maintains that best horticultural practices throughout the blueberry production pipeline—from preharvest all the way down through postharvest—will promote quality.

“During preharvest we need to have good control of the propagation system,” Giongo said. “We know that in blueberry, having certified, tissue culture plants is absolutely key to further production. Then there are a lot of environmental factors during harvest that contribute to the postharvest quality of the fruit that essentially are [related to] temperature and light.”

At Fondazione Edmund Mach, Giongo and her team conduct experiments on these factors in order to advance their plant selections. They look at growing plants in an open field versus soilless production, as well as winter production in the greenhouses or indoors. This allows them to control the light, temperature, and relative humidity fruit are exposed to during their development.

At postharvest, there are other factors that can contribute to quality and higher value blueberries in the market—sorting, sanitizing, metered supply, and the type of storage are all critical. Giongo’s different selections are tested in cold storage, in normal atmosphere, but also in modified atmosphere to separate the effects of storage.

“We do a lot of experiments in modified atmosphere,” Giongo said. “There are different [storage] recipes that are tailored for the different genotypes. Different packaging technologies—like modified atmosphere packaging (MAP bags)—have an influence on postharvest maintenance of blueberry quality.”

While all these factors are important, Giongo emphasizes that the most significant factor for postharvest quality is the genotype. Genotype makes, “the most impact and difference in the blueberry industry.”

“We started this work before VacCAP, but the project helped us a lot in analyzing these differences. We see that the dynamics of the fruit after storage changes a lot and changes are not in a singular direction, but can change according to the genotype,” Giongo said. “We can have an improved texture for some genotypes, or a detrimental texture for another genotype. So, getting this kind of high throughput phenotyping helps us clean [out unsuitable genotypes] before we get it to the growers.”

Giongo notes that the process of determining fruit quality occurs throughout the entire growing process. The team uses texture for essentially all of their screening of seedlings and the new materials that they introduce into evaluations. It is a very quick analysis in terms of operation, and they can process a high number of samples during a single day over the production season. This helps them get objective measurements that then assists in selecting proper material to move forward or sideline.

Texture analysis is also part of storage studies. The team makes an evaluation at harvest of all the fruit and then splits the samples so fruits are placed in either normal atmosphere or modified atmosphere storage depending on where they see the opportunity for a particular genotype. Then they analyze data and have a look at where the quality is in terms of texture.

“This means that we get segmentation of the quality and we address those that have a short shelf life in terms of our evaluated traits. Those that have a longer shelf life have a different destiny, they could be a bit more suitable for shipping or for longer periods in cold storage,” Giongo said. “We focus on the best selections in every category and we further phenotype for the other traits, which means flavor or other fruit quality characteristics.”

Giongo’s team has also developed different methodologies and techniques to help distinguish the genotypes’ subcomponents in order to understand why they fit into their respective segments.

“The [tools] are definitely more complex than the easy-to-use tools that growers may use, but they have helped us in understanding all the textural profiles in this fruit,” Giongo said. “All these evaluations that we made, and these methodologies that we have developed and published, we have started to correlate these data with simple and low-cost tools that might be much more accessible to growers looking to narrow down on fruit quality in a certain way.”

With all this work dedicated towards developing methods and facilitating breeding efforts to improve fruit quality traits, Giongo and her team also have to look at what outside factors could impact the future of blueberries and how their work will be influenced.

“Climate change is a huge part of the future and where blueberry will go, but differently than other crops. I think that in blueberry, we are in a privileged position because we are developing research at the same time as the industry,” Giongo said. “I think that the VacCAP project is an example of this, where the industry is going up very quickly, but also the research [community] is getting knowledge very quickly, having already known what was wrong in other crops. We are already doing positive things in terms of genetics and pre-breeding.”

Giongo notes that new technologies across the production pipeline are improving. Storage and energy-saving shipping methods are working towards a point where it can guarantee the consumer receives good product with less waste.

“All these different components of the blueberry production pipeline have a role,” Giongo said. “The key for the future is to get all this knowledge connected and spread.”